Abstract: Cave and tunnel complexes, which the Islamic State started constructing in the Hamrin mountain region well before the collapse of the caliphate, have become key to the group’s insurgent campaign in northern Iraq. With a new government yet to form following parliamentary elections in May 2018, there is a risk that focus in Baghdad will ebb on clearing out these mountain safe havens straddling Kirkuk, Salah ad-Din, and Diyala governorates.

Cave and tunnel complexes that the Islamic State started constructing well before the collapse of the caliphate have become a core element of the group’s asymmetric war fighting strategy. In the Hamrin mountain region, an area that straddles Diyala, Salah ad-Din, and Kirkuk governorates, the Islamic State has put considerable effort into constructing vast rural tunnel networks with weapons depots and foodstuffs well ensconced in both natural and man-made caves.1 The cave complexes, insulated with USAID tarps once intended for Iraqi internally displaced persons, are being discovered throughout this region.2 The caves serve as rugged redoubts from which the group wages guerilla war against the Iraqi state and its affiliated militias. As Iraqi and local ground forces supply geolocations, Combined Joint Task Force-Operation Inherent Resolve (CJTF-OIR) has been carrying out airstrikes aimed at dismantling the Hamrin tunnel network along with outlying bunker positions to smash the infrastructure undergirding the insurgency.3

This article is based in part on the author’s field reporting in Iraq in early 2018. Iraqi and pan-Arab news outlets have also reported on the ongoing counterinsurgency operations in the Hamrin Mountains. It is an area where al-Qa`ida in Iraq (AQI) in the last decade had a significant freedom of movement, even with a large U.S. troop presence in Iraq. It is now a significant safe haven for the Islamic State.4

In their efforts to flush out Islamic State militants, Iraqi Security Forces (ISF) and Shi`a militiamen incorporated under the Hashd al-Shaabi umbrella have been reaching the Hamrin foothills by Humvee and Toyota Hilux and then dismounting to scale higher elevations on foot while backed up by Iraqi Army helicopters.5 Sunni Arab tribal militias, known as Hashd al-Asha’iri, are also involved in security efforts around the Hamrin Mountains. In contrast to many Shi`a Arab fighters in Hashd al-Shaabi militias, Hashd al-Asha’iri are most often of local origin and allied to regional tribal leaders; they provide both indigenous intelligence and credibility in insurgency-affected districts of federally controlled northern governorates where fighters from the Shi`a-majority south are viewed as outsiders while also enlarging the security footprint of the ISF and the Hashd al-Shaabi. The current conflict in the greater Hamrin region is primarily a shadow war with little direct kinetic contact between opposing forces. Holding the high ground, jihadi militants have been able to retreat deeper into the hills as ISF and Hashd al-Shaabi expeditionary forces have approached at a distance from the lowlands.6

Difficult Terrain

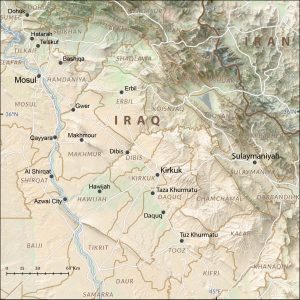

The topography of the Hamrin range, a ripple of the Greater Zagros Mountains located in western Iran, demarcates a natural boundary between northern and central Iraq.7 The range runs along a diagonal axis from northwest to southeast. Its northern reaches begin in the northeastern part of Tikrit district in Salah ad-Din Governorate. It then runs along the southwestern periphery of Al-Hawija and Daquq districts in Kirkuk Governorate (see Map 1) before reaching its southern limit at Lake Hamrin in Diyala Governorate’s Khanaqin district (see Map 2). On October 7, 2017, ISF and Hashd al-Shaabi announced that they had gained control of the mountains just two days after the liberation of Hawija.

8 Although Iraqi state and paramilitary forces may have temporarily cleared the area, militants who had been using the Hamrin for logistics as well as weapons storage and disbursement quickly remerged. Via its Amaq News Agency propaganda arma in June 2018, the Islamic State featured masked caravan members living a semi-nomadic existence in the Hamrin.b A notable component of Baghdad’s interest in clearing the Hamrin of militants is its desire to open up new trade links with Tehran after Kurdish forces were pushed out of Kirkuk in October 2017. The al-Abadi government has sought to secure the Hamrin mountain region and the adjacent Lake Hamrin basin in northeastern Diyala Governorate in order to transport crude oil by truck from Kirkuk’s abundant fields to the Iranian refinery of Kermanshah via the border gate of Khanaqin.9 Furthermore, Iran’s petroleum minister Bijan Namdar Zangeneh stated that Tehran desires a pipeline to be constructed through this region from Kirkuk directly to Iranian territory.10

The difficult-to-reach Hamrin mountain terrain is being used by Islamic State militants to train and organize attacks in nearby areas of northern Iraq.11 c Islamic State commanders and fighters have maintained training camps along the Hamrin range to learn and maintain the skills of their jihadi recruits.12 Additionally, Islamic State fighters have reportedly built medical facilities in the mountains to treat their wounded.

13 Vulnerable oil infrastructure in the fields abutting the Hamrin range is often a target of the group’s asymmetric attacks.14 The Islamic State employs sabotage tactics meant to inflame issues in Iraq that have remained unresolved since 2003. For example, on May 24, 2018, militants damaged power lines in the village of Barimah located north of the Bajii-Kirkuk road, which resulted in cutting off power to the Sunni Arab majority cities of Hawija and Tikrit in the midst of a heat wave.15 Public anger over power shortagesd has been further stoked by Islamic State militants sabotaging energy infrastructure in the Kirkuk-Diyala-Salah ad Din belt to further widen the rift between average Iraqis and the central government.

16 The attack on an otherwise significant village like Barimah signifies that the Islamic State cells that sought refuge in the Qori Chai river valley northeast of the Hamrin Mountains are now regularly launching operations out of this rugged area on an assortment of vulnerable targets in Kirkuk’s under-policed hinterlands. Militants launch nighttime attacks in villages where the Federal Police presence is either minimal or nonexistent.17

Map 1: Northeastern Iraq (Rowan Technology)

Digging In

The Islamic State’s construction of cave and tunnel complexes in northern Iraq began well before the demise of the Islamic State’s territorial caliphate, with many completed before that time.18 The Hamrin have a history as an insurgent redoubt. AQI, along with Ansar al-Sunna, and Jaish Rijal al-Tariqa al-Naqshabandiyya, used the mountains in a chaotic post-2003 Iraq in a manner analogous to the Islamic State’s current use.19 ISF and Hashd al-Shaabi brigades have discovered tunnels nestled deep in the mountains with generator-rigged electrical systems and makeshift water lines that they torch once they have been discovered and inspected20 to discourage the jihadis from returning to the area.21

Accurate ground intelligence by indigenous forces in locating the tunnels that are naturally concealed by the Hamrin range’s geologic formations is vital in coordinating supporting airstrikes. As an indication of the Islamic State’s longer-term planning, in February 2018, the ISF discovered a tunnel complex 20 kilometers south of Baquba, the seat of Diyala Governorate, outfitted with refrigerators with several months’ worth of food and washing machines all powered by a hidden solar grid above ground.22 The meticulousness with which the tunneling is carried out and the network’s food stores and ammunition caches indicate that the Islamic State laid the groundwork to sustain a protracted guerilla war while world attention focused on the Stalingrad-like battle for Mosul to the northwest. Well before Mosul fell to the ISF, Islamic State fighters were already launching attacks from their Hamrin hideouts in Diyala and Salah ad-Din governorates.23

In fact, the Islamic State’s tunneling efforts in some parts of Iraq long predated the battle for Mosul. In Diyala Governorate in particular, the Islamic State reverted to insurgency soon after its rapid territorial conquest of northern Iraq.24 Diyala was declared—at least publicly—entirely freed of Islamic State control by Staff Lieutenant General Abdulamir al-Zaidi on January 26, 2015, after the militants had been holding territory there for approximately six months.25 Likely calculating that its grip there was tenuous, the Islamic State bored tunnels in the Diyala sector of the Hamrin range as it occupied towns in the Lake Hamrin basin26 in the second half of 2014. In May 2015, Saraya Ansar al-Aqeedah, a Shi`a militia group under the banner of Hashd al-Shaabi, posted a video to its social media of Islamic State tunnels they were discovering in Diyala only months after ISF had declared the territory liberated.27

From the Mountains, a Mounting Insurgency

The tunnel and cave complexes formed part of wider preparations for the Islamic State’s insurgency. As the group was cleared at the village level—at least officially—in the governorates spanning the belt from Diyala to Ninewa connecting Iran to Syria between January 2015 and October 2017,28 the militants left booby-trapped homes in their wake, making numerous villages extremely perilous29 for returning IDPs as well as ISF not properly trained in high-risk ordinance removal. This IED-laying tactic has proven effective in making the region difficult to pacify.

This security vacuum allowed the Islamic State the space to revert quickly to insurgent tactics in Diyala while it was busy establishing administrative control in Mosul and other key cities elsewhere in Iraqi lands it had seized. The strategy the Islamic State had already implemented in Diyala was replicated in northern districts of Salah ad-Din and southern districts of Kirkuk once the key towns of Shirqat and Hawija were declared freed of Islamic State control in early fall of 2017.30

In many ways, Diyala has acted as an ethno-sectarian microcosm for security dynamics for the whole of Iraq. Its proximity to Baghdad, as well as the Iranian frontier, made it a priority for the al-Abadi government and Hashd al-Shaabi’s Iranian sponsors to control. Diyala was, for a time, the easternmost declared wilaya, or province, of the then-incipient caliphate project. It was the first significant area the Islamic State lost to state and sub-state forces in Iraq. Today, militants employ the Hamrin Mountains as a logistical lifeline stretching from Diyala to Kirkuk via Salah ad-Din.31

In July 2018, former Iraqi Minister of Interior Baqir Jabr al-Zubeidi said that he estimated the Islamic State controlled some 75 villages in Kirkuk, Salah ad-Din, and Diyala.32 These areas were never entirely taken under full control by the central government after the liberation of Hawija in early October 2017. In early 2018, frontlines hardened between the Islamic State and Federal Police in a string of agricultural villages southwest of Daquq town in Kirkuk Governorate.33

This past summer, vulnerable populations faced regular attacks in Kirkuk Governorate’s southern sub-districts.34 Religious minorities such as the Sufis35 and followers of the secretive syncretic Kakai faith36 along with local Sunni Arabs the Islamic State deems collaborators for cooperating with ISF37 continue to be at great risk from attacks by jihadis based in the low-slung Hamrin Mountains and the Qori Chai river valley, which begins near the tiny villages of Dabaj and Qaryat Tamur to the north of the Hamrin Mountains. The Qori Chai was described to the author as a “militant highway” whereby jihadis can traverse from the plains below the Hamrin northward to attack cities and towns in Kirkuk Governorate, which begins near the tiny villages of Dabaj and Qaryat Tamur to the north of the Hamrin Mountains.38

The Islamic State has been mounting regular assaults on pro-Baghdad Sunni Arab tribal militias across Kirkuk, Diyala, and Salah ad-Din governorates.39 In areas like Dibis district in northern Kirkuk Governorate that had been largely secured by Peshmerga until late 2017, the Islamic State claims to be launching nighttime raids against poorly funded Hashd al-Asha’iri encampments.40 The Islamic State’s assaults on minorities is patterned after past AQI tactics whereby vulnerable communities in the vicinity of the Hamrin Mountains and Lake Hamrin basin perceive themselves to be insufficiently protected by ISF, and ethno-sectarian tensions are further exacerbated as a result.41

Map 2: Diyala province, Iraq (Rowan Technology)

A Delicate Political Environment

The ongoing religio-political violence is taking place against the backdrop of the widely disputed May 12, 2018, parliamentary election, which saw Muqtada al-Sadr’s Sairoon Alliance receive the highest vote share. Sairoon ran on a nationalist platform focused on a long hoped for anti-corruption drive and the delivery of services to ordinary Iraqis in a coalition comprised primarily of the Sadrist Movement and Hizb al-Shwiyu’i al-Iraqi (Iraqi Communist Party). Sairoon then controversially formed a post-election alliance with the pro-Tehran Fatah alliance of Hadi al-Amiri, the leader of al-Badr organization, which forms the backbone of the Hashd al-Shaabi militia.e

When the al-Sadr-led Sairoon and al-Amiri’s Fatah allied themselves for a time in June 201842 as a matter of sheer pragmatism within Iraq’s fissured political spectrum, questions arose about the future of Hashd al-Shaabi. Two of Iraq’s most powerful men have starkly divergent views on the umbrella organization’s core task and purpose. This has potential implication for counterinsurgency efforts in the Hamrin Mountains given that the Hashd al-Shaabi have played a key role in these operations.

Al-Sadr espouses comparatively broader Iraqi nationalism blended with local Iraqi Shi`a identity politics while al-Amiri and other Shi`a militia leaders under Fatah have considerable fealty to Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali al-Khamenei and the revolutionary ideology of Wilayat al-Faqih (‘Guardianship of Jurist’).43 In the months since the election, the various blocs—primarily Sairoon, Fatah, Nasr, and former Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki’s State of Law Coalition—vying for power have failed to form a new, effective coalition government.

The political turmoil extends far beyond Baghdad. In post-KRG Kirkuk, the allegations of electoral fraud were perhaps most acute. There have been demonstrations from Arab and Turkmen communities alleging irregularities and demanding a recount44 after the late Iraqi president Jalal Talabani’s Patriotic Union of Kurdistan won the largest share of the Kirkuk vote even though Asayishf and Peshmerga forces withdrew from the city and the bulk of the governorate in mid-October 2017 following a reported deal between the Talabani family and Major General Qassem Soleimani, commander of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps’ Quds Force.45

The ongoing political stalemate in Baghdad coupled with anti-corruption protests in Iraq’s Shi`a-majority southern governorates46 has already, inevitably, diverted some focus away from the Hamrin operations as forces ranging from the elite Counter Terror Service to Hashd al-Shaabi’s Badr Organization have been dispatched to Basra to protect infrastructure and disperse protestors.47 Lacking the same visceral, unifying existential threat the territorial caliphate once posed to Iraqi Shi`a identity, the raison d’être for some of the most prominent pro-Iranian Hashd al-Shaabi leaders has shifted from war-fighting in northern and western Iraq toward an increased focus on evolving political and economic interests.48 Although ISF, Hashd al-Shaabi, and Hashd al-Asha’iri49 brigades have continued counterinsurgency operations in the Hamrin Mountains and other contiguous districts of northern Iraq, the current febrile political environment risks deprioritizing the fight against remaining Islamic State cells in the Hamrin Mountains.

Conclusion

Political turmoil in Baghdad risks taking the focus of Iraqi political leaders away from clearing militants from the Hamrin mountain range, which has emerged as key redoubt for Islamic State fighters and a launching pad for the group’s insurgency in northern Iraq. Baghdad lacks a coherent strategy for dealing with militants hiding in the depths of the Hamrin and nearby Makhoul Mountains, the Lake Hamrin basin, and the craggy Qori Chai river valley northeast of the Hamrin Mountains. It is in these remote areas and this difficult terrain that the jihadis have survived to fight another day in a battlespace far less familiar to their opponents. As political elites in Baghdad and Najaf jockey to form a new government, the still-serving al-Abadi government’s low-intensity war is making little headway.

In a further possible distraction to tackling militants in the Hamrin Mountains, ISF and Hashd al-Shaabi are also contending with a burgeoning protest movement railing against endemic corruption and power shortages in cities across the underserved southern governorates.50 The stakes are high. If the Islamic State continues to strengthen its position in the Hamrin Mountains, its insurgency could spread wider across Iraq’s federally administered northern governorates. CTC

Derek Henry Flood is an independent security analyst with an emphasis on the Middle East and North Africa, Central Asia, and South Asia. He is a contributor to IHS Jane’s Intelligence Review and Terrorism and Security Monitor. Flood’s research for this article included travel to Kirkuk Governorate in February and March 2018. Follow @DerekHenryFlood

Substantive Notes

[a] The Amaq News Agency is an official node of the Islamic State’s media arm. See Daniel Milton, Pulling Back the Curtain: An Inside Look at the Islamic State’s Media Organization (West Point, NY: Combating Terrorism Center, 2018).

[b] Islamic State militants are also active in the nearby Makhoul Mountains, located between Baiji and Shirqat due west of the Tigris River in Salah ad-Din Governorate.

[c] Islamic State fighters who conduct attacks in Kirkuk Governorate’s settled areas have visually dissimulated into Iraqi society by shaving their beards and dressing like ordinary citizens while no longer traveling in convoys with brash Islamic State insignias. Mustafa Saadoun, “Islamic State awakens sleeper cells in Iraq’s Kirkuk,” Al-Monitor, July 5, 2018.

[d] From Basra up to Kirkuk, chronic power shortages during high-temperature periods have remained a festering domestic political issue in Iraq. See Sudad al-Salhy, “Al-Abadi rivals sabotage Iraq’s power lines and fuel protests,” Arab News, August 7, 2018.

[e] Fatah is essentially a political extension of the pro-Iranian wing of the Hashd al-Shaabi militia network.

[f] In contrast to the Peshmerga who function as the KRG’s forward military force, the General Security Directorate operating under the KRG’s Ministry of Interior, known as the Asayish, is responsible for security and intelligence gathering regarding terrorism and other threats to the wider Iraqi Kurdish-controlled region. See “General Security (Asayish),” Kurdistan Region Security Council website.

Citations

[1] Author interview, security source at Kirkuk governor’s compound, March 2018; Haider Sumeri, “Dai’sh goes underground as peace persists,” 1001 Iraqi Thoughts, June 4, 2018.

[2] “Escaped members of ‘Daesh’ built tunnels in the mountains,” Akhabar Al-Aan News, March 18, 2018.

[3] “Military airstrikes continue against ISIS terrorists in Syria and Iraq,” United States Central Command, February 9, 2018; “Military airstrikes continue against Daesh terrorists in Syria and Iraq,” United States Central Command, February 23, 2018.

[4] Anthony H. Cordesman and Adam Mausner, “Withdrawal from Iraq: Assessing the Readiness of Iraqi Security Forces,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, August 2009.

[5] “New military operation in Iraq near Iranian border,” Al-Hurra News, June 6, 2018.

[6] “Al-Hashd al-Shaabi control the area south of the Hawija pocket,” War Media Team-Hashd al-Shaabi YouTube channel, October 3, 2017.

[7] Charles Keith Maisels, The Near East: Archaeology in the ‘Cradle of Civilization’ (London: Routledge, 1993), p.126.

[8] “Iraq recaptures Hamrin mountains from Daesh,” Anadolu Agency, October 7, 2017.

[9] “Iraq plans military operation to secure oil route to Iran: security sources,” Reuters, February 5, 2018.

[10] “Iran at OPEC: Kirkuk pipeline would increase current oil exports 10-fold,” Rudaw, June 22, 2018.

[11] Halo Mohammed, “ISIS in Hamrin Mountains plotting election attacks,” Rudaw, April 28, 2018.

[12] “ISIS training camp in Hamrin Mountains destroyed,” Baghdad Post, December 27, 2017; “The PMU destroys a camp for Daesh terrorists in the mountains of Hamrin,” Al-Ghadeer News, December 27, 2017.

[13] “ISIS tunnel, medical center seized in Kirkuk,” Baghdad Post, August 1, 2018.

[14] “47 explosive devices seized in Alas oil field in Salahuddin’s Tikrit,” Baghdad Post, April 12, 2018; Araz Mohammed, Amir Ali Mohammed Hussein, and Ben Van Huevelen, “Ajil oil field targeted in latest insurgent attacks,” Iraq Oil Report, July 18, 2017.

[15] Sangar Ali, “Iraqi cities face complete power outage after IS targets towers in Kirkuk,” Kurdistan 24, May 25, 2017.

[16] “Kirkuk-Diyala electricity lines sabotaged again; Iraq blames ‘terrorism,’” Rudaw, August 8, 2018.

[17] Author interviews, residents of Kirkuk, Salah ad-Din, and Diyala governorates conducted in Erbil Governorate, March 2018.

[18] Sumeri; author review of Iraqi and pan-Arab media coverage.

[19] Dashty Ali, “Extremists Go From Mosul To The Mountains,” Niqash, July 27, 2017.

[21] “10 ISIS guesthouses torched as operation in Hamrin Mountains continues,” Baghdad Post, June 25, 2018.

[22] “The tunnels are a ‘sanctuary’ in hot spots in eastern Iraq,” Xinhua, February 3, 2018.

[23] “Insurgent attacks continue in northern Iraq,” Iraq Oil Report, January 27, 2017.

[24] Adam al-Atbi, Araz Mohammed, Amir Ali, and Samya Kullab, “Rising insurgency hits Diyala, despite security efforts,” Iraq Oil Report, June 7, 2017.

[25] “Iraqi forces ‘liberate’ Diyala from ISIS: officer,” Agence France-Presse, January 26, 2015.

[26] Mira Rojkan, “ISF Discover Another IS Tunnel in Hamrin Lake,” Bas News, February 6, 2017.

[27] “A tunnel was found in the hills of Hamrin by Saraya Ansar al-Aqeedah,” Saraya Ansar al-Aqeedah YouTube channel, May 19, 2015.

[28] “Iraqi forces ‘liberate’ Diyala from ISIS: officer;” Nadia Riva, “Iraqi Forces announce liberation of Hawija city center,” Kurdistan 24, October 5, 2017.

[29] “Military engineering officer killed in explosion of booby-trapped house in southern of Salah ad-Din,” Al-Ghad Press, November 4, 2015; Ahmed Aboulenein, “Iraq returning displaced civilians from camps to unsafe areas,” Reuters, January 7, 2018.

[30] “Iraq forces oust IS from northern town in drive on Hawija,” Agence France-Presse, September 22, 2017; Maher Chmaytelli, “Islamic State driven out of last stronghold in northern Iraq,” Reuters, October 4, 2017.

[31] “Security forces cut off central roads for logistical support of Islamic State cells in the Hamrin Basin northeast of Baquba,” Al-Hurra, August 10, 2018.

[32] Baxtiyar Goran, “IS controls 75 villages in Kirkuk, Salahuddin, Diyala: Former Iraqi Interior Minister,” Kurdistan 24, 2018.

[33] Author interview, Kirkuk city, Iraq, March 2018.

[34] “IS Attacks Village in Southern Kirkuk,” Bas News, June 26, 2018.

[35] Amaq, March 24, 2018.

[36] “Militants seize Kakai village, demand allegiance to Islamic State,” Rudaw, June 26, 2018.

[37] “Four federal police were injured in an attack on the “Daesh” southwest of Kirkuk,” Al-Sumaria TV, April 12, 2018.

[38] Author interview, resident of Tuz Khurmatu conducted in Erbil Governorate, March 2018.

[39] “Six killed and four wounded from the tribal Hashd by Islamic State in Hawija district southwest of Kirkuk,” Al-Rafidain Television, July 1, 2018.

[40] Amaq News Agency, June 13, 2018.

[41] Barry Leonard eds., Measuring Stability and Security in Iraq (Collingdale, PA: Diane Publishing Co., 2008), p. 25.

[42] Ahmed Aboulenein, “Iraq’s Sadr and Amiri announce political alliance,” Reuters, June 12, 2018.

[44] Emad Matti, “Iraqis protest in Kirkuk over alleged voting fraud,” Associated Press, May 16, 2018.

[45] Author interview, Kirkuk resident, conducted in Erbil Governorate, September 2017.

[46] “Basra: Protesters Took Back to Streets after One Killed by Police,” Bas News, August 16, 2018.

[47] Baxtiyar Goran, “Iraq declares state of emergency amid ongoing violent protests,” Kurdistan 24, July 14, 2018.

[48] “Iraq’s Paramilitary Groups: The Challenge of Rebuilding a Functioning State,” International Crisis Group, July 30, 2018; Kosar Nawzad, “Militia leader calls for change in Iraq’s system of government,” Kurdistan 24, August 22, 2018; Maher Chmaytelli, “Iranian-backed Shi’ite militia chief aims to lead Iraq,” Reuters, May 8, 2018.

[49] Ghazwan Hassan, “Suicide attack kills six Sunni fighters in northern Iraq: police,” Reuters, August 22, 2018.

[50] Edward Yeranian, “Casualties Reported After Iraqi Security Forces Fire on Protesters,” Voice of America, July 15, 2018.

CTC Center